What is Negative Space in Photography?

Negative space in photography refers to the empty, open, or uncluttered areas surrounding the main subject. This space isn’t just filler; it’s a deliberate compositional tool that draws attention to the subject, creates balance, and evokes specific emotions. By intentionally leaving parts of the frame unoccupied, photographers can transform ordinary shots into powerful visuals. Whether you’re shooting portraits, landscapes, or products, understanding negative space elevates your work from cluttered to compelling.

In essence, negative space contrasts with positive space—the area occupied by the subject itself. The interplay between these two defines the image’s structure. For instance, a lone tree against a vast sky uses the sky as negative space to emphasize isolation. This technique isn’t new or niche; it’s foundational to strong composition, applicable across genres like wildlife, street, or food photography.

Photographers often confuse negative space with mere emptiness, but it’s relative. What appears as background in one context can become negative space when it supports the subject without competing. The goal is to make the space purposeful, contributing to the story rather than detracting from it.

Defining Positive and Negative Space

Positive space is the focal point—the subject that grabs the viewer’s eye, such as a person, animal, or object. Negative space is everything else: the surrounding voids that provide context and emphasis. This duality is crucial because negative space isn’t inherently “negative” in a bad sense; it’s a counterbalance that amplifies the positive.

Consider a simple analogy: in a crowded room, a single spotlight on one person makes them stand out. The darkness around them acts as negative space, isolating and highlighting. In photography, this could be a bird in flight against a blank sky or a product on a plain white background.

To clarify the distinction, here’s a comparison table:

| Aspect | Positive Space | Negative Space |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The main subject or elements of interest | The surrounding empty or subdued areas |

| Role | Attracts immediate attention | Provides breathing room and emphasis |

| Visual Weight | High; dominates the frame | Low; supports without overwhelming |

| Examples | A portrait subject, a car in motion | Vast sky, plain wall, blurred background |

| Impact on Composition | Creates focus and narrative | Enhances balance, scale, and emotion |

This table illustrates how the two spaces interact. Balancing them ensures the image feels harmonious rather than empty or chaotic.

The Principles of Using Negative Space Effectively

Mastering negative space requires intentionality. It’s not about randomly leaving space but strategically composing to enhance the subject. Key principles include:

Creating Breathing Room

Allow the subject to stand out by isolating it from distractions. Surround it with uncluttered areas, like a simple background, to give the viewer’s eye a rest. This separation prevents visual clutter, making the subject pop. For example, in portrait photography, position the person against a uniform wall rather than a busy street.

Establishing Scale and Isolation

Use large expanses of negative space to convey size or solitude. A small subject against a massive backdrop, such as a hiker on a mountain ridge with endless sky, emphasizes vulnerability or grandeur. This technique manipulates perception, making the subject appear diminutive yet significant.

Applying the Rule of Thirds

Integrate negative space with the rule of thirds for balanced compositions. Divide the frame into a 3×3 grid and place the subject at an intersection point, filling the remaining two-thirds with negative space. This creates asymmetry that’s visually engaging. Avoid centering the subject unless the negative space is evenly distributed for symmetry.

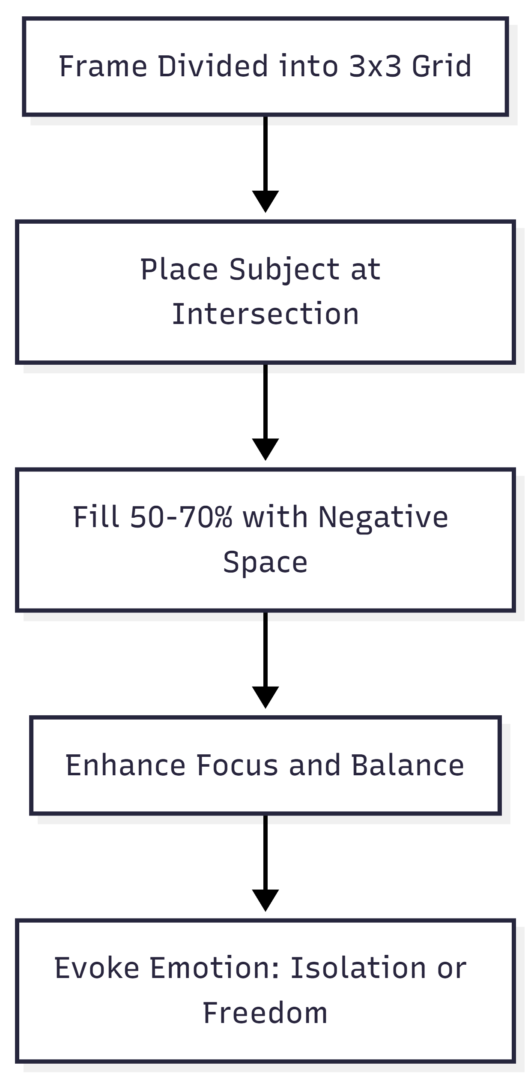

Here’s a simple diagram illustrating the rule of thirds with negative space:

This flowchart shows the step-by-step process for incorporating negative space.

Directing the Viewer’s Eye

Leave more negative space in the direction the subject faces or moves. This “leading space” implies motion and prevents the composition from feeling cramped. For a person looking right, allocate more space on the right side to suggest forward progression.

Simplifying Backgrounds

Choose or create backgrounds that serve as negative space: blank walls, textured but uniform surfaces, or out-of-focus areas via shallow depth of field (e.g., f/1.8 aperture). Blur distractions to ensure the background supports rather than competes. In food photography, a plain tabletop around a dish acts as negative space, highlighting textures and colors.

Balancing the Frame

Aim for negative space to occupy at least 50% of the frame, but adjust based on intent. Too much can make the image feel vacant; too little overcrowds it. Test by cropping in post-processing to see how adjustments affect visual weight.

No strict rules exist—negative space is stylistic. The key is ensuring it’s not “dead” space but adds to the narrative. Strong subjects hold attention amid emptiness, while clean edges prevent minor distractions from breaking the flow.

Examples of Effective Negative Space

Real-world applications demonstrate negative space’s power. Consider a single bird silhouetted against a vast sky: the sky’s emptiness isolates the bird, evoking freedom. Or a person against a plain wall, positioned off-center—the wall’s uniformity draws eyes to facial expressions.

In landscapes, a solitary car on a winding road with surrounding neutral terrain uses negative space to imply journey. The empty areas guide the eye along leading lines, enhancing dynamism.

Portraits benefit too: a subject on the left with expansive space on the right suggests introspection. In urban settings, blurred buildings as negative space focus on a central figure, conveying scale amid city vastness.

For wildlife, a leopard in a zoo enclosure with cropped space around it emphasizes captivity without distracting fences. In product shots, a clean background surrounds an item, making it ideal for e-commerce.

These examples show versatility: negative space works in color or black-and-white, with minimal or textured backgrounds, as long as it complements the subject.

When Negative Space Falls Short

Not every attempt succeeds. Common pitfalls include:

- Misalignment: Slanted elements, like uneven stairs in a shot of a person ascending, disrupt harmony. Straighten in post or recompose for clean lines.

- Distracting Elements: Diagonal fences or cut-off features (e.g., an animal’s ear) pull focus. Crop tighter or reposition to eliminate.

- Competing Focal Points: Bright objects, like red balloons near a couple, steal attention. Tone down or remove in editing to restore balance.

- Unclear Subject: If negative space overwhelms or confuses what’s primary, the image fails. Ensure the subject is strong enough to anchor the frame.

Analyze online images: search for “negative space photography examples” and critique what works. This sharpens your eye for composition.

Conveying Emotions Through Negative Space

Negative space isn’t neutral—it shapes mood. Light, airy spaces evoke positivity: hope, joy, freedom. A woman in a joyful pose against bright sky and sea suggests new beginnings.

Dark or vast negative space conveys negativity: loneliness, despair. A curled figure in bleak, empty surroundings amplifies vulnerability.

Sinister tones arise from black expanses, like shadows around a menacing subject, heightening intensity. Color and tone matter: muted backgrounds enhance calm, while stark contrasts build tension.

Experiment: the same subject with varying negative space alters interpretation. A centered person in equal emptiness feels stable; off-center implies unease.

The Broader Importance of Negative Space in Composition

Negative space isn’t a trick—it’s core to all photography. It flattens elements, treating shapes equally for harmony. In food photography, a burger as a circle balances with surrounding “empty” areas, including props like wedges that provide context without dominating.

Train your vision: invert scenes, seeing spaces as solids. Practice with overhead shots where foreground and background distinctions are clear.

Visual weight matters: adjust negative space to balance. Cropping or repositioning shifts emphasis, as in portraits where more space on one side enhances emotion.

In genres like wedding photography, pillars frame a bride, creating negative space that amplifies serenity. Wildlife shots use blurred foliage to isolate animals, conveying wildness.

Ultimately, negative space makes subjects “grow” by surrounding them with context. A spot on white paper becomes a story through infinite emptiness.

Advanced Techniques and Considerations

Depth of field controls negative space: shallow blurs backgrounds, turning busy scenes into supportive voids. Wide apertures (f/1.4-f/2.8) excel here.

Lighting influences: soft light on negative space keeps it subtle; harsh light adds texture without distraction.

Post-processing refines: dodge/burn to adjust tones, clone out minor flaws.

For genres:

- Street: Urban voids isolate moments.

- Macro: Blurred surroundings magnify details.

- Abstract: Negative space becomes the subject.

Tools like 50mm or 85mm primes (around $200-$500) aid control, with fast apertures for bokeh.

Final Thoughts on Mastering Negative Space

Negative space transforms photography by emphasizing subjects, balancing frames, and evoking emotions. Practice intentionally: compose with 50%+ space, integrate rules like thirds, and critique failures.

It’s not about rules but purpose—if it tells your story, it’s right. Experiment across shoots to discover its potential. With time, negative space becomes instinctive, elevating your work to professional levels.

For more, explore composition tips in related resources.

Please share this What is Negative Space in Photography? with your friends and do a comment below about your feedback.

We will meet you on next article.

Until you can read, Lightroom Shortcuts Every Photographer Needs to Know